FATE Research Group: From Why to What and How

When the public started getting access to the internet, search engines became common in daily usage. Services such as Yahoo, AltaVista, and Google were used to satisfy people’s curiosity. Although it was not comfortable using search engines because users had to go back and forth between all the search engines, it seemed like magic that users could get so much information in a very short time. At that time, users started using search engines without any previous training. Before search engines became popular, the public generally found information in libraries by reading the library catalog or asking a librarian for help. In contrast, typing a few keywords is enough to find answers on the internet. Not only that, but search engines have been continually developing their own algorithms and giving us great features, such as knowledge bases that enhance their search engine results with information gathered from various sources.

Soon enough, Google became the first choice for many people due to its accuracy and high-quality results. As a result, other search engines got dominated by Google. However, while Google results are high-quality, those results are biased. According to a recent study, the top web search results from search engines are typically shown to be biased. Some of the results on the first page are made to be there just to capture users’ attention. At the same time, users tend to click mostly on results that appear on the first page. The study gives an example about a normal topic: coffee and health. In the first 20 results, there are 17 results about the health benefits, while only 3 results mentioned the harms.

This problem led our team at the InfoSeeking Lab to start a new project known as Fairness, Accountability, Transparency, Ethics (FATE). In this project, we have been exploring ways to balance the inherent bias found in search engines and fulfill a sense of fair representation while effectively maintaining a high degree of utility.

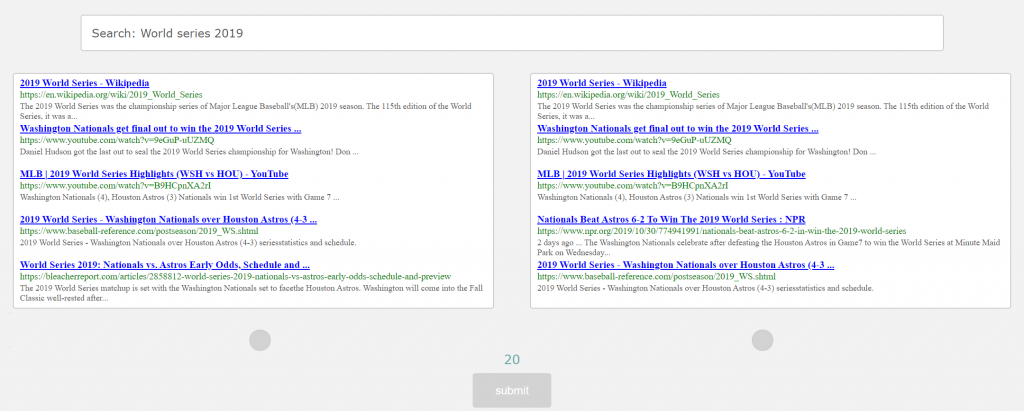

We started this experiment with one big goal, which is to improve fairness. For that, we designed a new system that shows two sets of results, both of which are very similar to Google’s dashboard. (as illustrated by picture below). We have collected 100 queries and top 100 results per query from Google in general topics such as sports, food, travel, etc. One of these sets is obtained from Google. The other one is generated through an algorithm that reduces bias. The system has 20 rounds. The system gives a user 30 seconds on each round to choose the set they prefer.

For this experiment, we asked around 300 participants to participate. The goal is to see if participants can notice a difference between our algorithms and Google. The early results show that participants preferred our algorithms more than Google. However, we will discuss more in detail as soon as we finish the analysis process. Furthermore, we are in the process of writing a technical paper and an academic article.

Also, we have designed a game that looks very similar to our system. This game tests the ability to notice bad results. It gives you a score and some advice. In this game, users can also challenge their friends or members of their families. To try this game, click here http://fate.infoseeking.org/googleornot.php

For many years, the InfoSeeking Lab has worked on issues related to information retrieval, information behavior, data science, social media, and human-computer interaction. Visit the InfoSeeking Lab website to know more about our projects https://www.infoseeking.org

For more information about the experiment visit FATE project website http://fate.infoseeking.org